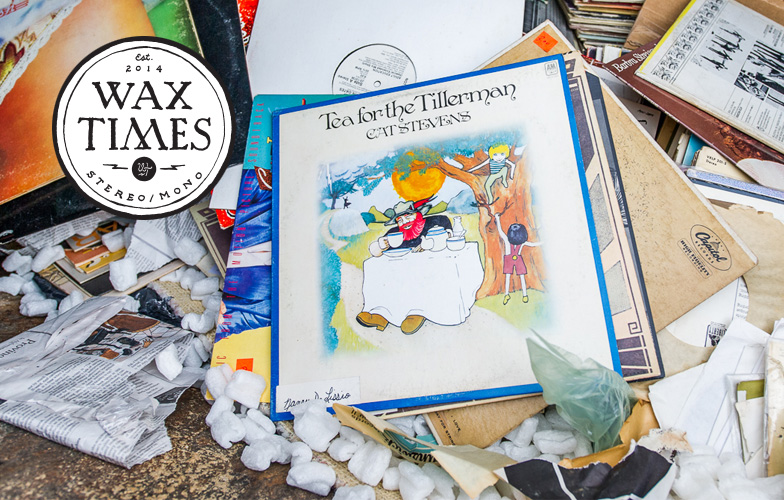

Nothing about throwing records away felt good and the worst part was that I knew someone would probably take them if offered, even if only to dispose of them later after they realized there was no value left in any one of them. But it was my job.

The first time it happened I wasn’t prepared for the answer but someone else was. “No, we don’t have any free records.” It made sense, stores don’t survive by giving away product they could otherwise sell but then there’s always the leftovers that have to be reckoned with. Actually saying no to a customer who asks for anything free seemed more like an obligatory response that reinforced the retail mentality of everything has a price, but it was also a lie. Records were routinely thrown away just as grocers and restaurateurs deliberately toss their unserved food or goods nearing expiration into the garbage rather than giving them away. At this point, providing free music in analog format hasn’t risen to the occasion of being a social issue and people are still throwing away records.

The goodwill of store owners oscillates on a scale of it’s own with some providing sanctuary for customers of every socioeconomic position while others are completely allergic to clientele that can be dismissed as non-customers the minute they walk through the door. Music doesn’t have a specific market segment because it’s a universally accepted form of entertainment, art and culture that has continuously developed and influenced everyday life even when the experience is a passive one. No matter the case, music as art has value but estimating the cost of an experience continues to remain as elusive as a free record and the only progress that can be measured is by use of historical price indexes adjusted for inflation.

Our nearest high-profile comparison comes from 2007, when Radiohead experimentally released their album In Rainbows, essentially, for free. Both sides, Radiohead and mainstream media, revealed different data sets that captured the dichotomous result. The band and management claimed it a success with consumers who downloaded the album paying an average price for the music. Opponents accused Yorke and friends of debasing a market already struggling to stay afloat amidst the onslaught of a complete digital music apocalypse that we’re still struggling to make sense of. True fans purchased a physical copy, maybe even the deluxe box, but it’s value as experiment verse testament of good faith and the value of music is debatable.

More than once I was asked to dump records and because I was getting paid it was part of my job to do so. On one occasion, a bin of vinyl found itself lodged in the dumpster. It was so full that neither my coworker nor myself could lift it out and one of us had to climb in to retrieve it. Truthfully, the albums that went out back were so far gone most of the time that they really were garbage but something always made it feel a little taboo. No matter how many millions of copies of an album are out there, throwing a record away goes against everything I felt a record store stood for, especially when it was routine to have customers ask for those albums we didn’t even want to or were able to try and sell. It felt a little too much like Fahrenheit 451 in the sense that there was both the availability of free records but they were disposed of and lied about.

As it turned out, the records that were dumped generally found their way back into the store or into the hands of someone willing to retrieve them from that last stop on their journey to the final destination. In the middle of the night and even during daylight hours, rummaging through the dumpster behind the store was tolerated to an extent. Some crate diggers were so hardcore that their convictions pushed them to engage in diving regularly, hoping to pull a rare 78 from the depths just like habitual lottery players know they have a winning 7-digit combination every time they buy a ticket. The only part that bothered me was when they would bring the records back into the store in an attempt to sell them to us for cash or trade as if we didn’t know what we’d thrown away the night before.

Only one local record store makes it a habit to leave small piles of albums by the door before tossing them out. It satisfies the curious vinyl pedestrian who isn’t quite sure what they’re doing in a record store other than musing about the idea of getting into vinyl and looking for that way way in with little investment. The box sometimes has a sign but otherwise gives no indication that makes it clear that the contents within are free of charge and the question/answer exchange between clerk and inquiring customer always seems a bit awkward. At least it’s an opportunity for someone that doesn’t involve getting really dirty.

Running a record store works just as any other retailer would when dealing in both new and used merchandise. Separating the wheat from the chaff and selling what you can as quickly as possible doesn’t always leave a lot of time for good faith or social responsibility. Inventory that is unsellable takes up room, a lot of room, and record stores fill up quickly with piles of albums that will never see a price tag. Some local distribution centers for larger donation-based entities deal by the pound because they simply cannot take the time to individually price and sell albums as it’s not part of their core business. This is where the overlap between those that want free records and the businesses that have free records exists.

After witnessing enough pilfering, it was interesting to note that there wasn’t just one type of person that went through the records out back. When album covers peaked out above the height of the bins it was a sign that those were free and anyone interested could take as much as they wanted and that’s exactly what they did. I was honestly happier to see someone giving one last chance to those albums for whatever reason they used to rationalize the act that most anyone else would turn away with in disgust than to see more records filling up wastelands.

Innovation has become a leading topic among those interested in social responsibility and with music at the forefront of various ongoing debates, maybe Radiohead were right to experimentally provide their album free of charge. If we continue to profit from every commodity in life even our garbage will retain value. We must decide when we can say yes instead of turning people away from what they want and that which we knowingly have to give away.

Feature Image: Jazz Guy via Flickr

Help make Wax Times better Next Post:

Maintaining the value of original pressings