Direct to disc recording was the predominant recording method prior to the invention of magnetic tape, churning out 78rpm discs for decades. Paired with the introduction of the LP in 1948, recording to magnetic tape began to supersede direct to disc methods. The benefits that tape offers have a lot to do with its ability to be cut, spliced, re-recorded or otherwise edited during production. With a direct to disc setup, recording proceeded through an entire LP side with no breaks. Everyone had to play precisely, without any mistakes or a lacquer was scrapped and the process started over.

In 2001, Audio Engineer Robert Auld took part in a temporary resurrection of direct to disc recording technology at the Audio Engineering Convention as part of an effort to highlight the once favored process. Auld’s experience, as part of the production chain assisting Al Grundy, is documented with audio samples available on his site. Auld was responsible for microphone placement, live mixing via tube console and generally ensuring that the live signal captured was “worth recording on the cutting lathe.”

The constraints placed on equipment and pressure on musicians to perform at this level seems a little unreasonable. Since editing or overdubbing are out of the question, whatever sound was captured will be there for better or for worse. Ultimately, the flexibility and affordability of magnetic tape and, later, digital recording pushed direct to disc practices out of favor. The late 70’s saw a brief resurgence in direct to disc album offerings and today, companies like Capsule Labs continue working in this traditional process. A promotional video below shows clips of a direct to disc session in Capsule Labs’ studio making all of this a little bit easier to understand.

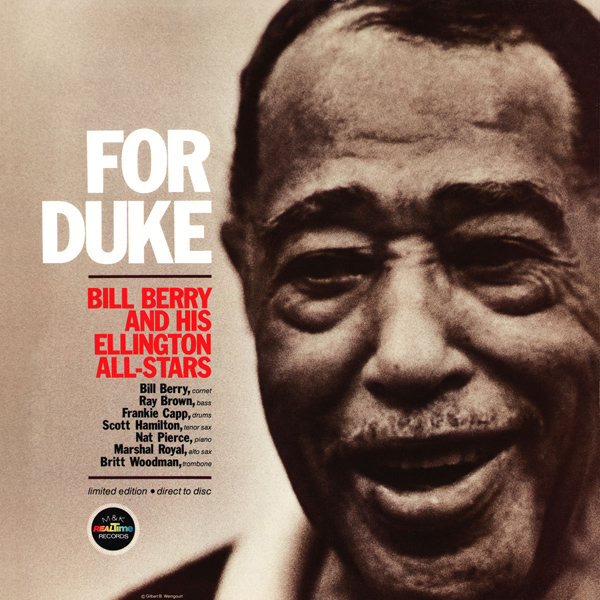

Finding an album that captures the magic of the direct to disc process isn’t easy. It wasn’t but 6 months ago when I was introduced to For Duke by Bill Berry and his Ellington Allstars. The album is something like a Kind of Blue of the direct to disc market, a crowning achievement and sonic masterpiece that occupies a space of exclusivity among every other records I own. Starting off with “Take the ‘A’ Train”, the album’s fidelity creates a huge soundstage that envelops the listener, fully immersing them in the set. Audiophiles covet this release. It’s hard to come by and when you do find it, it’ll cost you but the price is well worth it. For me, it is the first and last word in the direct to disc discussion and the album impresses every single person that hears it, warming up skeptics and transforming tepid opinions into 100% believers.

Lists of famous direct to disc records are out there but most of them are on lists for reasons aside from the recording technology behind their production. Aside from For Duke, I can’t point to any other release as significant of an example of direct to disc recording. Articles from the New York Times hint at the authenticity of sound but don’t really provide any guidance to specific titles to purchase. Then there are larger lists like that from Arthur Salvatore, which include the Bill Berry album but do not exclusively focus on direct to disc records either. Michael Fremer points to the Bill Berry album as well in a review of Shortcake, a later release from the same musician:

“Berry’s most famous ‘audiophile’ record is the M&K Sound Realtime Direct to Disk recording For Duke (RT-101) which I think still fetches big bucks, and is worth the money.”

Good sounding records are out there and they aren’t necessarily the product of a direct to disc session. The practice does capture, in essence, a very true sense of a live performance free of the artifacts common among taped sessions. From a purely experiential perspective, I’m glad to own a copy of For Duke.

Making a Wantlist with Discogs Next Post:

Miles Davis, DeVotchKa and Black Friday